The Online Payments landscape in India is unique. There is deeper penetration and a faster adoption rate than in some of the more technologically advanced nations. The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) has made a significant impact on both P2M (Peer to Merchant) and P2P (Peer to Peer) transactions by introducing various payment platforms such as UPI, RuPay, Bharat Bill Payment System, etc. The usage of these platforms has grown in leaps and bounds owing to the increasing number of smartphone users and cheap internet accessibility.

Now the RBI has launched the Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). What impact will CBDC create, and will CBDC add meaningful value to the Indian digital payments ecosystem?

UPI: a success but still a long way from cashless economy

While UPI handled $1 trillion in transactions, India’s currency-in-circulation (CIC) to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio is the third highest in the world. CIC stood at ~INR 32 lakh crore, i.e., ~14% of GDP, as of June 2022. In fact, in FY22, the RBI spent almost INR 5,000 crore on printing, distributing, and storing currency.

So, the key question is whether CBDC can do more than UPI to push India towards a completely cashless economy.

CBDC Vs UPI

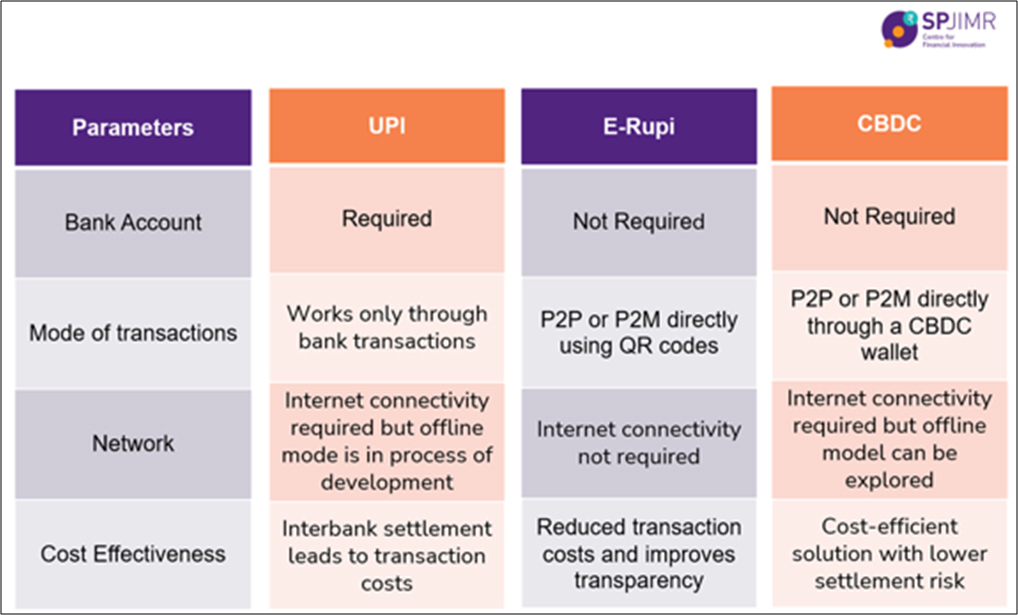

The main difference between UPI and CBDC is the requirement for a bank account. India has one of the world’s largest unbanked populations, with around 190 million Indians not having a bank account and nearly 90 million bank accounts lying dormant. While UPI works on transacting through bank deposits, CBDCs can be transacted from P2P or P2M directly through a CBDC wallet after eKYC registration. This has the potential to ensure deeper financial inclusion among economically backward segments without bank accounts.

Further, UPI requires an active internet connection and a smartphone. An offline model for transacting CBDCs (via Bluetooth or Near Field Communication) can be explored. China and the Bahamas have experimented with CBDCs with offline usability. Japan has been exploring offline CBDCs on a basic phone as well as on a smartphone. According to the NITI Aayog report, only 55 out of every 100 people have an internet connection. An offline model can greatly help India tap individuals living in remote geographic locations with limited internet access; thus increasing financial inclusion.

Also, the government is estimated to spend approximately INR 1,500 crore towards the cost of RuPay debit cards and UPI transactions in FY22. CBDC could be more cost-efficient as it eliminates the need for interbank settlement. Thus, reducing transaction costs related to settlement infrastructure.

CBDC Vs e-RUPI

e-RUPI is a voucher-based payment system that works via SMS or QR Codes, launched by the Government of India. It is mainly used for Direct-Benefit Transfer (DBT) schemes. e-RUPI was launched to reduce leakages and eliminate middlemen while implementing DBT schemes such as LPG subsidies, fertilizer subsidies, old-age pensions, the transfer of wages in MGNREGA, etc. e-RUPI does not require a bank account or an internet connection and is purpose- and person-specific. However, since its launch in 2021, there have been issues building sufficient infrastructure and an ecosystem for it, with only 11 national banks currently supporting e-RUPI. Regional banks are yet to associate with the platform. Due to higher on-field problems such as server issues and a lack of financial literacy, the platform has not yet reached the needy as anticipated.

Programmable CBDCs also work in a similar fashion to e-RUPI. They specify an end-use by the person who is transferring the money. For example, food subsidies credited to a beneficiary’s CBDC wallet by the government could only be used to purchase rations from registered shops. As CBDC will be launched at a pan-India level and garner high credibility due to its equivalence to physical cash, the adoption rate by key stakeholders such as banks, merchants, and beneficiaries might be higher in comparison to e-RUPI. Further, the cost of building a separate ecosystem for e-RUPI will also be eliminated as CBDCs serve multiple functions, including DBTs.

Could CBDC act as a master solution?

Due to the rapid growth in the online payment landscape and the existing mechanisms working successfully, it is premature to predict how effective CBDC’s adoption will be. However, it is important to note that CBDC, if implemented correctly, can provide a simpler, more transparent, cost-efficient solution with lower settlement risk. Further, CBDC provides multifold benefits such as programmable payments for Direct-Benefit Transfers, cross-border remittances, retail payments, MSME lending, and offline payments under one umbrella. But the government and RBI will have to go the extra mile to implement CBDC with the right technological infrastructure and awareness drive. Whether it will potentially provide a single transactional solution and help India further financial inclusion hinges on its implementation success.

Source: Author’s Contributions